The Open Public Meetings Act (“OPMA”)

Title X mandates that any meeting of the Municipality (Council or BOE) must be made in public, upon notice and with an opportunity provided to members of the public to speak on any matter they wish.

Whether at the council, Board of Education, Planning Board or Environmental Commission, there’s a chance to speak directly to those in power to decide issues, before those issues are voted upon.

But there’s another principle at play with the public’s right to speak: namely, the right of everyone to have business conducted by their elected representatives.

Imagine what would happen if someone didn’t like something the council was proposing and lined up enough people to speak for hours until we could no longer hold a vote?

In essence, it would be a veto by a filibuster (sometimes called the “heckler’s veto“). Therefore, while I’ve rarely seen it employed, the ability to cut off speakers at a reasonable point exists, to ensure that the business of the public is properly capable of being conducted, while still protecting the right of the public to speak.

The Open Public Records Act (“OPRA”)

OPRA has a similar issue in terms of balancing priorities.

The law was enacted to enable public access to public records. If you want to see Ordinance 33-2018, all you need to do is request it and the clerk’s office is obliged, under statutory authority to provide a copy to you within 7 days. You can even get it via email.

OPRA is a wonderful law, in terms of moving forward with transparency.

But like OPMA, it has the ability to be abused. We’ve seen this in the past.

The Government Research Council (“GRC“) has dealt with this as well.

In a decision on Complaint 2012-82, the GRC was asked to decide what to do when the request was for:

“All e-mails between Executive Director Mr. William Fellenberg to NJCU OPRA Officer Alfred Ramey”

You see, this isn’t asking for the email sent regarding X. It’s just a request for everything.

OPRA is meant to allow access to public documents, but it’s not meant to enable snooping through files for anyone who wishes to do so.

The GRC said the same thing:

“The Custodian further states that the Complainant’s request Item No. 5 is vague in terms of the subject matter and time period to which the e-mails

were sent.”

In the final determination the GRC ruled:

“The Complainant’s OPRA requests are overly broad because they fail to identify specific government records sought, and are thus invalid under OPRA. See MAG Entertainment, LLC v. Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control, 375 N.J. Super. 534 (App. Div. 2005), Bent v. Stafford Police Department, 381 N.J. Super. 30 (App. Div. 2005), New Jersey Builders Association v. New Jersey Council on Affordable Housing, 390 N.J. Super. 166 (App. Div. 2007) and Schuler v. Borough of Bloomsbury, GRC Complaint No. 2007-151 (February 2009). See LaMantia v. Jamesburg Public Library (Middlesex), GRC Complaint No. 2008-140 (February 2009).” (emphasis added)

“This is the final administrative determination in this matter.”(emphassis added)

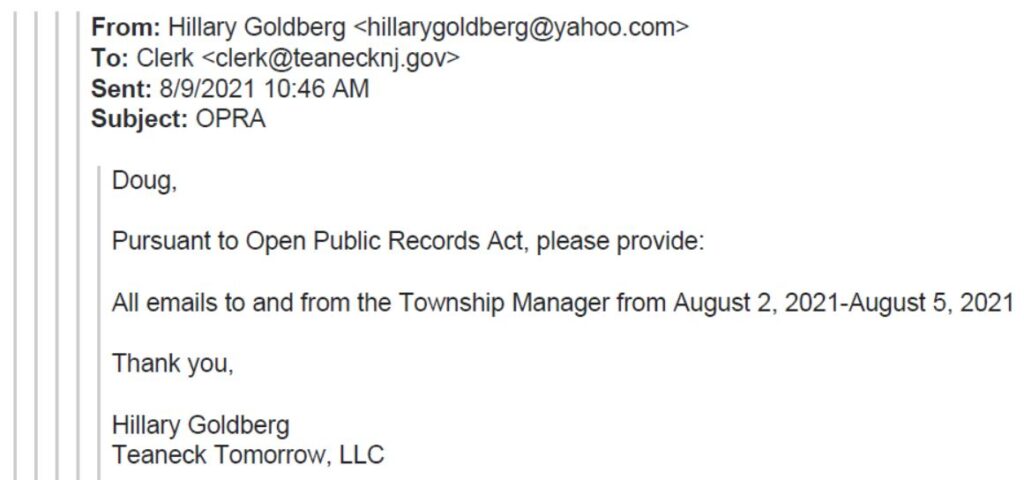

The Teaneck clerk’s office has been advising Council regarding the “very busy” OPRA caseload, so I requested information on the OPRA requests that were taking so much time to work on.

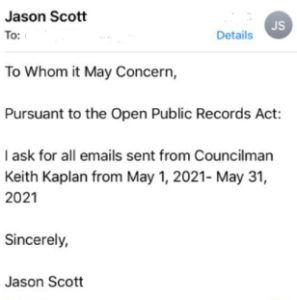

I happened upon a few OPRA requests that looked like this:

I’m all for transparency, but the balance of the equities here should require “Jason Scott*” to merely state what he or she is interesting in obtaining from the public record.

In MAG Entertainment, LLC v. Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control, 375 N.J. Super. 534 (App. Div. 2005), the Appellate Division stated quite clearly:

Under OPRA, as under its predecessor statute, the Right to Know Law, N.J.S.A. 47:1A-2 to -4… the Legislature continued “the State’s longstanding public policy favoring ready access to most public records.” Serrano v. South Brunswick Tp., 358 N.J. Super. 352, 363 (App. Div. 2003).”

But they go on to say:

“OPRA is a public disclosure statute… Its purpose is to inform the public about agency action, not necessarily to benefit private litigants…. Importantly, “OPRA limits its definition of “government record” to:

any paper, written or printed book, document, drawing, map, plan, photograph, microfilm, data processed or image processed document, information stored or maintained electronically or by sound-recording or in a similar device, or any copy thereof, that has been made, maintained or kept on file in the course of . . . official business . . . or that has been received in the course of . . . official business . . .”

You simply cannot use OPRA, as per the Appellate Division, to go on a fishing expedition or to help find leads for reporters / bloggers.

See MAG Entm’t, LLC v. Div. of Alcohol Beverage Control, 375 N.J. Super. 534:

While OPRA provides an alternative means of access to government documents not otherwise exempted from its reach, it is not intended as a research tool litigants may use to force government officials to identify and siphon useful information. Rather, OPRA simply operates to make identifiable government records “readily accessible for inspection, copying, or examination.” N.J.S.A. 47:1A-1. Even then, inspection is subject to reasonable controls, and courts have inherent power to prevent abuse and protect the public officials involved. See DeLia v. Kiernan, 119 N.J. Super. 581, 585 (App. Div.), certif. denied, 62 N.J. 74 (1972). In fact, if a request would substantially disrupt agency operations, the custodian may deny it and attempt to reach a reasonable solution that accommodates the interests of the requestor and the agency. N.J.S.A. 47:1A-5(g).

What happens if a person asks for all documents?

On this score, the Government Records Council (Council), the administrative body charged with adjudicating OPRA disputes, N.J.S.A. 47:1A-6, has explained that “OPRA does not require record custodians to conduct research among its records for a requestor and correlate data from various government records in the custodian’s possession.” Reda v. Tp. of West Milford, GRC Complaint No. 2002-58 (January 17, 2003). There, an individual sought information regarding a municipality’s liability settlements but did not request any specific record. Ibid. In rejecting the request, the Council noted that OPRA only allows requests for records, not requests for information, and therefore, it is “incumbent on the requestor to perform any correlations and analysis he may desire.” Ibid.

(Appellate Division)

What about a one-month period requesting all emails, like the example above?

The Appellate Division cites a case called Capitol Information Ass’n v. Ann Arbor Police, 360 N.W.2d 262, 263 (Mich. Ct. App. 1985), saying:

“the court upheld the denial of a plaintiff’s request for public records that included “all correspondence with all federal law enforcement/investigative agencies . . . that pertain to persons living in Ann Arbor, Michigan . . . .“Even though the request was confined to a relatively short period of time, the court characterized it as “absurdly overbroad” and explained that “[p]laintiff had to request specific identifiable records; it failed to do so here.” Id. at 264.”

Thus the court concludes:

“We do not interpret OPRA any differently. Under OPRA, agencies are required to disclose only “identifiable” governmental records not otherwise exempt. Wholesale requests for general information to be analyzed, collated and compiled by the responding government entity are not encompassed therein. In short, OPRA does not countenance open-ended searches of an agency’s files.”

This has been affirmed subsequently. See, for example, ELIZABETH MASON v. CITY OF HOBOKEN et al.

“As we emphasized in both MAG Entertainment and Bent, OPRA is not intended to be used as a fishing expedition or as a research tool to compile unknown documents.” (emphasis added)

Can you identify a particular record here?

No, me neither.

Note: A lawsuit was filed on Tuesday, September 7, 2021, by Hillary Zaer Goldberg requesting similar documents.

You can read the complaint** here: BER-L-005899-21 Complaint

This is a “fishing expedition” or “research tool” to compile unknown documents, in the words of the Court in Mason v. Hoboken.

And now our clerk’s office is inundated with requests just like the one above. Some come from similarly fictitious names, requesting a month of emails at a time for everyone on council.

This is not what transparency was supposed to mean when OPRA was created.

And while I feel strange arguing against the law I champion, I also have a duty to ensure that the work of the public is capable of being accomplished.

* There does not seem to be a resident by the name “Jason Scott”, and OPRA requests may be submitted anonymously or under a pseudonym.

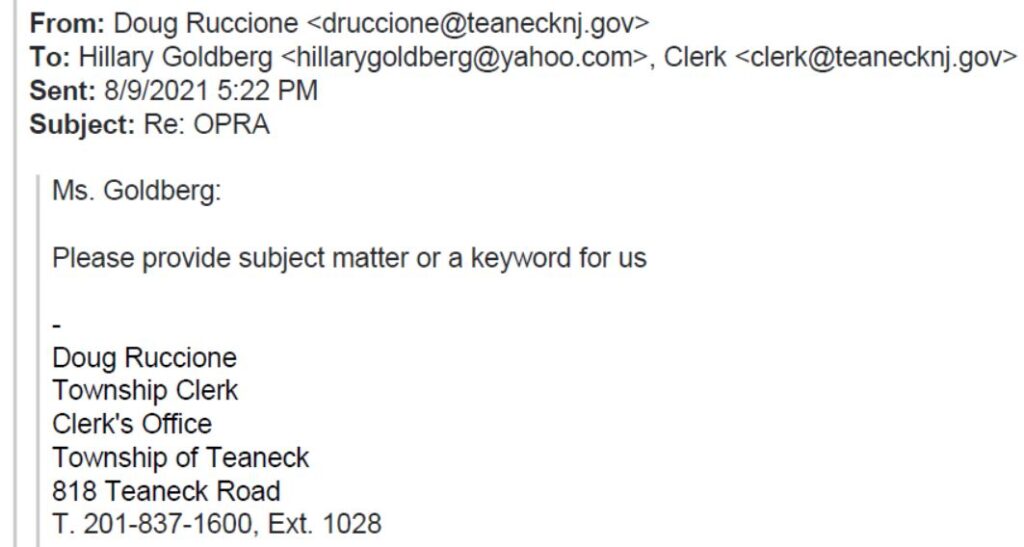

** The lawsuit filed by Hillary Zaer Goldberg against the Township of Teaneck started with this request:

Recall that the NJ Appellate Division quoted a MI case stating: “Even though the request was confined to a relatively short period of time, the court characterized it as “absurdly overbroad” and explained that “[p]laintiff had to request specific identifiable records; it failed to do so here.”

The clerk responded by requesting keywords in accordance with the well-established decisions cited above:

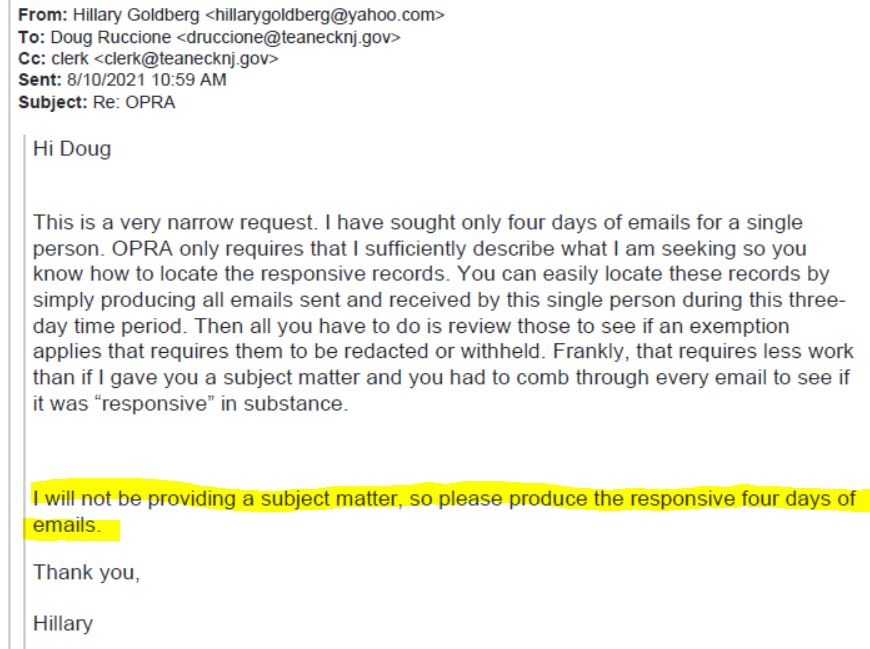

Ms. Goldberg demanded the documents and would not provide any keywords to describe the documents sought.

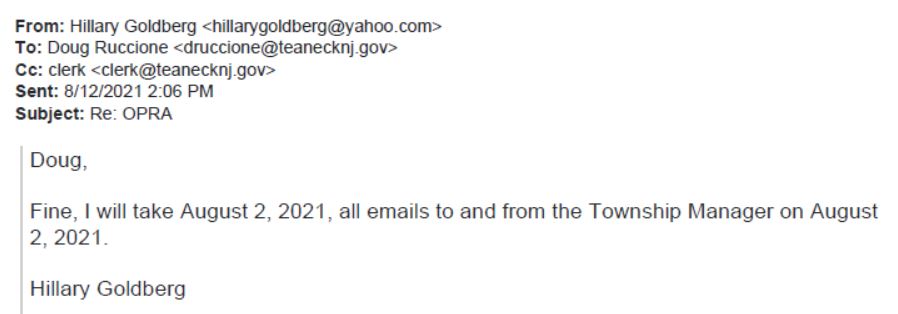

On August 12th, Ms. Goldberg modified the request to all emails sent or received, on August 2nd, again not including any particularity of what documents were being sought.

Whether it’s:

ELIZABETH MASON v. CITY OF HOBOKEN et al. (“OPRA is not intended to be used as a fishing expedition or as a research tool to compile unknown documents.”

or

MAG Entm’t, LLC v. Div. of Alcohol Beverage Control (“Even though the request was confined to a relatively short period of time, the court characterized it as “absurdly overbroad” and explained that “[p]laintiff had to request specific identifiable records; it failed to do so here.”)

and

(“Wholesale requests for general information to be analyzed, collated, and compiled by the responding government entity are not encompassed therein. In short, OPRA does not countenance open-ended searches of an agency’s files.”)

the result will be the same… you can’t use a public transparency law to find blog material. The clerk’s office isn’t your personal assistant. They are the custodian of records for the municipality.