James Payne’s journey is not one of those well known stories, but perhaps it will again become one, here in Teaneck.

Payne moved from Virginia to Englewood, NJ’s fourth ward in 1947 and he studied engineering, becoming a Mason and joining Local 28. Several years later, he would start a move to Teaneck.

Payne moved from Virginia to Englewood, NJ’s fourth ward in 1947 and he studied engineering, becoming a Mason and joining Local 28. Several years later, he would start a move to Teaneck.

By all accounts, Mr. Payne was a soft spoken, hard working, industrious resident seeking the best life he could here for his family.

As per a 2012 article by Jay Levin, Theodora Lacey said that Payne was “a pioneer – not in the civil-right sense, but in the sense of wanting to make a difference in his own life”. Mr. Levin notes that Payne himself agreed generally with the aims of civil rights struggles fought by the NAACP, CORE and the Teaneck schools integration efforts, but he acted for no groups and no organizations backed him.

James Payne merely wanted to build a house in what he thought was a nice location.

While his son, Keith Payne said his father never “thought himself a trailblazer”, he clearly changed the trajectory for Teaneck’s population, one brick at a time. And in doing so, he set off a chain of events.

The beginning of integration in Teaneck

In 1950, Teaneck was 99% white. It wasn’t an accident. Lincoln school in Englewood’s Fourth Ward was 99% black at the time and as black members of Englewood’s 4th Ward started to look beyond the Englewood border into Teaneck, the Teaneck Town Council erected what would become a tree lined buffer zone.

In an article published in the Bergen Record in February, 1969, Reginald Damerell, explained where he got the impetus to write Triumph in a White Suburb, the book chronicling Teaneck’s voluntary integration, which features an entire chapter about James Payne:

“One day I was in the Teaneck Library and I happened to see an aerial photograph of Teaneck,” Damerell explained, “I couldn’t figure out why there were paved roads through the woods, roads with curbs. In a sense, that set me off on the book.”

Teaneck may have had a few black residents, but they were segregated to the other side of the buffer, where they were socially isolated to Englewood, as opposed to Teaneck.

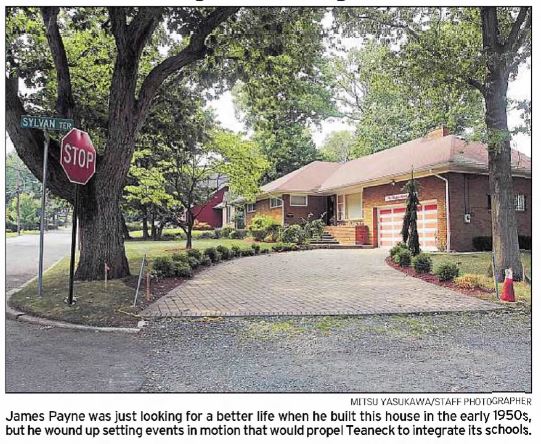

Then, in 1951, Payne, a contractor, found a piece of land that interested him, which happened to be across the buffer zone. At the time, white real estate agents in Teaneck would not sell a plot to a black man in this area, but Payne went through a real estate broker in Bergenfield who made all the necessary arrangements with the owners in California. The land, beyond Teaneck’s buffer zone, now belonged to a black man, but Payne hadn’t yet saved up enough money to start building a home, so it went largely unnoticed — until 1953, when the Board of Adjustment granted him a variance to build his home.

Purchase secured, and funds available, Payne started to work on his home after finishing his foreman & mason jobs. He would work on his home Saturdays, Sundays and many evenings, starting with the foundation.

When word spread there were those in the immediate area that wanted to buy him out. One neighbor offered more than the list price. Payne declined. And when that failed, many tried to thwart his efforts by any means – including vandalism.

“Boys from eight to eighteen systematically wrecked everything they could at his building site. Repeatedly he saw them running away as he drove up, to find his lumber broken up or missing, and rocks and dirt thrown in his excavation. Once, his sewer line to the street was smashed. Another time, his water had been turned on and the foundation was flooded. He had to take precautions each night before leaving that are usually unnecessary in building a house.”

“Sometimes as he worked, a couple of the boys would come and stand among the trees and watch him mix concrete. He told them one day he was going to bring them baseball gloves, and a bat and ball. He suggested they organize a team and play in the open field across the way. Payne did not know that among Teaneck’s many proud “firsts” was a summer recreation program under the guidance of a full-time, professional recreation director. Payne spent fifteen dollars on equipment and the boys accepted it, but their destruction continued. He tried offering two of the oldest boys a couple of dollars a week to keep the others from doing damage.”

- Triumph in a White Suburb (chapter 2)

[In his book, Triumph in a White Suburb, which details Teaneck’s voluntary integration of the school system, the second chapter is devoted to James Payne. It’s worth the read – and it’s available at the Teaneck Public Library.]

The damage at Payne’s home continued until he was able to afford workers to be at the site during the day. In 1954 when Mr. Payne moved into his home, Dammeral says that more than half the homes (24 out of 40) on Hubert, Buffet, and Endicott Terraces, and those nearest Payne on Englewood, would be sold to Black families.

His son, Keith Payne said that he recalled his father telling him “that at one time he was sleeping with a gun underneath his pillow, that’s how scared he was”.

Unable to stop him from moving into the neighborhood, white residents started to sell their homes. By the time James Payne finished constructing his house, three black families had been living close by and dozens more white families were looking to exit the area.

A decade later, the influx of black families, predominantly to one section of town, would lead civic groups to join efforts against blockbusting and panicked selling. The efforts of those groups, also led to Teaneck becoming the first town to voluntarily desegregate our schools.

It’s with much thanks to Mr. Payne and others like him, that we have a diverse and thriving township today. If you have suggestions for others that should have their history highlighted, please let me know in the comments.

If anyone wishes to see the home James Payne built, its located at 173 Englewood Avenue, near Sylvan Terrace.